The Black Bronx: Realizing “A Dream Deferred”

Local residents and people all around the world have identified the Bronx as the city’s “worst” borough for decades. When it’s featured in movies such as The Warriors, Rumble in The Bronx, and Escape from the Bronx, it is depicted as dangerous, dirty, and impoverished. The Bronx is known for its hard streets that have cultivated some of the country’s best-known criminals, men like John Gotti, Godfather of the Gambino Family. When it’s brought up in conversation, it is perceived to be an accomplishment to say you survived growing up or living in the Bronx and eventually managed to leave. But what if I told you that the Bronx used to be a sanctuary for people of color who wanted to escape the clutches of neo-slavery and racism in the South and begin a new life as fully empowered American citizens? What if I told you that the Bronx was actually the preferable option for a higher quality of life for families in New York in comparison to present-day popular locations like Harlem? What if I told you that the Bronx “was a place where black migrants from Harlem found an opportunity to raise children nurtured by strong churches, racially integrated schools, and business districts that contained some of the most vibrant music venues in all of New York City” (Naison and Gumbs xi). Would you still view the Bronx in the same light if you knew the truth about its history?

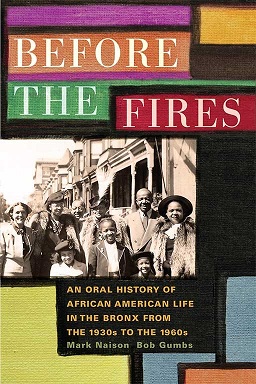

Mark Naison and Bob Gumbs’ Before The Fires: An Oral History of African American Life in the Bronx From 1930s to the 1960s presents the direct experiences of black Bronxites who lived in the Bronx from the 1930s to the 1960s. In their own words, these men and women recount their perceptions of growing up in a borough that was built on the foundations of diversity, integration, family, community involvement, education and religious worship. Through the oral histories of seventeen African Americans and one white American, Naison and Gumbs show how life in the Bronx during this period shaped these subjects into the people they became. The interview subjects were chosen from the Morrisania section of the South Bronx because this was an area where African Americans were allowed to migrate (at the time, many other parts of the borough remained closed to black residents). Mark Naison, a professor at Fordham University, began this project after being approached by Dr. Peter Derrick, the chief archivist at the Bronx County Historical Society, who told him about the demand of local residents for information on the subject, which the Society did not then possess. The oral history project began with Naison’s acquaintances and then evolved through word of mouth; only the sharpest and most richly detailed interviews were chosen for publication from the oral histories that were collected.

Mark Naison and Bob Gumbs’ Before The Fires: An Oral History of African American Life in the Bronx From 1930s to the 1960s presents the direct experiences of black Bronxites who lived in the Bronx from the 1930s to the 1960s. In their own words, these men and women recount their perceptions of growing up in a borough that was built on the foundations of diversity, integration, family, community involvement, education and religious worship. Through the oral histories of seventeen African Americans and one white American, Naison and Gumbs show how life in the Bronx during this period shaped these subjects into the people they became. The interview subjects were chosen from the Morrisania section of the South Bronx because this was an area where African Americans were allowed to migrate (at the time, many other parts of the borough remained closed to black residents). Mark Naison, a professor at Fordham University, began this project after being approached by Dr. Peter Derrick, the chief archivist at the Bronx County Historical Society, who told him about the demand of local residents for information on the subject, which the Society did not then possess. The oral history project began with Naison’s acquaintances and then evolved through word of mouth; only the sharpest and most richly detailed interviews were chosen for publication from the oral histories that were collected.

Throughout Before the Fires, the South Bronx is described as a safe and nurturing environment where family and community involvement was encouraged and diversity in schools and integration in communities evolved without resistance. Victoria Archibald-Good describes a childhood that seems almost utopian by today’s current standards, especially when considering she was raised in the Patterson Houses, which are located in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx, between Third Avenue and Morris Avenue on East 149th Street: “I remember the camaraderie and the supportiveness and the nurturing that I got from not only my own family but from folks in the building who weren’t blood relatives. The saying ‘It takes a village to raise a child’—it was absolutely true in the Patterson Houses” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 145). Archibald-Good moved from Harlem to the Bronx in 1950 and remembers the Bronx to be filled with kids that all lived close by and attended the same schools. She also speaks of summer camps provided to children in the projects that took them on field trips to museums, baseball games, Coney Island, and the planetarium. For Archibald-Good, the Bronx was a land of family and unity where everyone protected one another, and the community was, contrary to popular beliefs, self-sustaining.

Another subject in the book, Vincent Harding, details the importance of education in the community. He shares his school experiences and remembers travelling to the library on Southern Boulevard to read and borrow books (the library was open seven days a week). While Harding was an avid churchgoer, he found much of his inspiration and encouragement from his teachers: “I think that my experience at Morris [High School] helped me become somebody who had a vision of a community that united people of different racial and religious backgrounds” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 13).  Harding describes Morris High School in dramatically different terms than one would today. “There was [a] tremendous emphasis on culture. We had Sunday-afternoon programs called Lyceum programs where you had poetry readings, singing, quartets, piano presentations, and speeches” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 8). Going to school on a Sunday is unheard of today unless for special reasons, let alone to work with musical instruments or give speeches, especially at Morris, which continues to be a struggling school. Not only does this anecdote reveal drastic distinctions with Bronx communities that exist today, it also highlights the borough’s potential to produce individuals that reach higher levels of achievement in society, such as Harding, who became an activist, theologian, and a distinguished historian, or Gene Norman, another subject in this book, who was the former chairman of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Harding describes Morris High School in dramatically different terms than one would today. “There was [a] tremendous emphasis on culture. We had Sunday-afternoon programs called Lyceum programs where you had poetry readings, singing, quartets, piano presentations, and speeches” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 8). Going to school on a Sunday is unheard of today unless for special reasons, let alone to work with musical instruments or give speeches, especially at Morris, which continues to be a struggling school. Not only does this anecdote reveal drastic distinctions with Bronx communities that exist today, it also highlights the borough’s potential to produce individuals that reach higher levels of achievement in society, such as Harding, who became an activist, theologian, and a distinguished historian, or Gene Norman, another subject in this book, who was the former chairman of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The oral history of James Pruitt and his family, who moved from Harlem to the Bronx in 1932 for financial reasons, shows the salience of a thriving community made up of hard-working parents and local figures. Pruitt’s father worked at the post office, and his mother was a stay-at-home mom with a college education. Pruitt describes this fact with optimism, as it was an aspect he saw throughout his community: “She had a college education, but in those days men were proud to say, ‘my wife raises our family and provides for the home, and I provide for the family’” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 77-78). Socially, Bronxites supported one another, and families were built upon common traditions that fostered strong foundations in the community, where Bronxites also helped elect neighbors to political office, such as Councilman Wendell Foster (see Naison and Gumbs 78).

Not only were these Morrisania communities integrated and thriving, the schools were also leading examples of diversity, filled with programs that developed students’ interests in the arts and sports. Morris High School was the school many of the Bronxites from Before the Fires attended. James Pruitt, specifically, received his education in the Bronx and became a teacher at Morris High school after graduating from there. He describes his high school with great enthusiasm: “Morris was one of the most wonderful high schools in the city. They had an academic curriculum, they had a commercial curriculum, and they had a general curriculum. I’m a retired teacher, but comparing myself to the teachers I had there, I had some of the most skilled individuals that I’ve ever seen anywhere” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 83). The interviewees from Before the Fires speak of how Bronx students were extremely invested in their progress, and how the schools provided much support to flourishing students and children interested in achieving more.

For example, Joseph Orange and his family moved to the Bronx from Harlem, in 1941, and he discovered his passion for music in a diverse school culture. The school diversity in parts of the South Bronx was a marvel when you consider the national racial climate of the 1940s and 1950s. The integration of the schools is apparent in Joseph Orange’s account of his time as a student in junior high: “But I don’t recall a lot of racial tension in the Bronx at that time. My classes were about fifty-fifty black and white, and I don’t ever remember a racial incident” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 106). It was inside these diverse classrooms with devoted teachers where Joseph Orange, a child of West Indian parents, would begin his musical journey, but it was on the streets of the Bronx that Orange would begin his musical career. Throughout the Bronx, Orange followed up-and-coming artists and attended shows, leading him to meet the famous Barry Rogers at the Triton Club near Hunts Points Palace. Later, Orange went on to work with Eddie Palmieri, Lloyd Price, Slide Hampton, Al Gray, Lionel Hampton, and Herbie Mann, with whom he would go on tour around the world.

Having lived in the Bronx for over fifteen years now, I consider myself a Bronxite, but my experience has always made me question why a borough so close to the wondrousness and beauty of Manhattan could be so troubled by poverty and crime. I attended Intermediate School 158 in the Melrose section of the Bronx. This school is walking distance from the Forest Houses and Morris High School, two locations that appear throughout Before the Fires. I actually grew up in the area of the Bronx where the majority of the Bronxites from Before the Fires did, and the contrast of their experiences with mine is vast. While the Bronx is filled with a deep sense of culture today, it lacks true diversity, as many white and Jewish residents left the borough during “The Great White Flight” in the 1970s. The schools are overcapacity, as I remember classes that had around 28-30 students in them and teachers were poorly adapted to the working conditions they were under. The sense of community seems to be disjointed, as many communities are towered over by huge apartment buildings that make neighborhoods overcrowded and integration difficult. While the Bronx no longer has the decay that stemmed from the decade of fires that spread across the city in the 1970s, the borough still lacks the proper attention and maintenance it deserves and which it received in the 1950s and 1960s.

The period chronicled in this book comes before the U.S. government began instituting programs that would cripple the Bronx and send it into a period of fierce fires, vandalism, vagrancy, crime, and neglect. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) jumpstarted this deterioration in the Bronx by redlining areas that residents (mostly white and affluent) then moved out of, causing investors to avoid putting money back into the worn-down buildings and neighborhoods (Gonzalez 111). In Evelyn Gonzalez’s urban history, The Bronx, she explains how the FHA instituted programs that would force Bronxites to resort to any means for economic survival, even burning down their own apartment buildings for insurance money or payment from landlords. This is what led to a decade of fires throughout the Bronx, branding the Bronx with a stigma of violence and devastation that most people believed was caused by the Bronxites themselves. Within this book, however, Naison and Gumbs reveal true-life accounts of the society that was flourishing in the Bronx during the 1940s and 1950s, and which appears to be almost the opposite of the Bronx that I live in today.

Yet the Bronx of Naison and Gumbs’ African-American subjects is not irrecoverable. Indeed, it corresponds to a proven formula for successful community building. As Joseph Orange puts it:

There was a great deal of achievement. People had personal successes, and that doesn’t happen in a vacuum. That happens because of family, it happens because of community, it happens because of school, it happens because of churches. It happens for a multitude of reasons, and all those reasons existed in that community at that time. It’s troubling to me that it all disappeared, and there’s some guilt too (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 113).

The guilt that Orange is speaking of is probably for the conditions that his Bronx is in now, and the way the communities of the Bronx that were once thriving, have fallen apart. According to Evelyn Gonzalez, however, this tide has been turning, as the Bronx has currently been experiencing a renaissance.

The dream of a totally flourishing Bronx has been a dream deferred for too long. But what Naison and Gumbs’s book shows is that it is also a dream that was realized during the twentieth century, and one that can be re-realized again in the twenty-first. Joseph Orange describes the Bronx in a fashion that is very emblematic of current misconceptions about the borough. “I think the Bronx is a unique place, like some other historical places you’ve read about where African Americans achieved a great deal that has been written out of history. I think the Bronx is in danger of being like that” (qtd. in Naison and Gumbs 112-113). I would take Orange’s comment a step further by saying that the Bronx today is like that, a place where African Americans achieved a great deal that risks being written out of history. Naison and Gumbs are beginning a conversation that needs to be had about the way the community and local government can identify policies and initiatives that will cause the Bronx to flourish, not diminish. The editors of this book are showing that the Bronx has the foundation to continue to be a melting pot of different races, cultures, and religions that can support growth and productivity as it once did so well.

Works Cited

Gonzalez, Evelyn. The Bronx. Columbia University Press, 2006.

Naison, Mark D., and Bob Gumbs, editors. Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life in the Bronx from the 1930s to the 1960s. Fordham University Press, 2016.

As one who grew up in the Bronx during the 40’s ,50, & 60’s l really appreciate this article. I also went to JHS 40 and was a classmate of Robert Gumbs. I now live in Maryland ,however l still have family living there. I’ve seen the changes for the better. New buildings going up. I don’t think they still have real NEIGHBORHOODS like we did growing up where everybody knew and looked out for one another. Those of us who grew up in the Morrisania section of the Bronx were blessed to have the experience of a well integrated neighborhood. My grands and great grands will never have that experience and it saddens me.