A Spray-painted Response to Nuyorican Poetry in Hunts Point

If you’ve ever heard of Hunts Point in the Bronx, New York, there’s a good chance you associate it with their produce market, or a great place to get cheap auto-body work done. Nicknamed “The Point,” the area has seen its fair share of ups and downs in its community and physical aesthetics. Long known for its tenements, drug dealers and prostitution, Hunts Point is generally not on the list of touristy places to visit in New York. That’s where TATS Cru, a well-known and highly skilled group of Latin@ graffiti artists, comes in. Armed with spray cans, good music and a bond formed and understood through graffiti art, TATS Cru has taken Hunts Point and turned it into their own open-air gallery, with a goal of enriching the area’s history and current diverse community. In so doing, they’ve offered a spray-painted response to some of the problems and longings expressed in Nuyorican poetry of previous decades.

One can easily view The Point protruding out into the East River on any map of the Bronx. According to staff writer Sandra E. Garcia of The Bronx Journal, Hunts Point is named after Thomas Hunt, one of the first settlers to occupy the area during the 1670s. More than a century later, the poet Joseph Rodman Drake was buried in Hunts Point. Like the names of many other prominent historical Hunts Point figures, you can find Drake Street, a favorite of TATS Cru, just around the corner from where Drake is buried. The names of many of the streets in Hunts Point offer a forgotten insight into the area’s rich history. But you don’t only have to look up at the street signs to discover the area’s history. While walking down by Hunts Point Riverside Park, you are bound to feel the historical changes in the surface under your feet, where you’ll find railroad tracks and cobblestones in spots where the cement has weathered, weakened and worn away, revealing pieces of yesterday’s Hunts Point.

Moving forward through the years and into the mid-1900s, Hunts Point became known for being the “skipped” area of the Bronx, since the local highway literally skips over it, making it that much harder to travel to and from. Because of this, it became an area known for its tenements, drug dealers and prostitution. Recalling distant memories of Puerto Rican New York’s past “El Barrio,” the lack of attention and care for the area made it a breeding ground for illegal activity. Such activity included groups of children and teens marking their territory through graffiti paint (I hesitate to refer to all of it as art, as the social issue became the use of graffiti paint to vandalize or inappropriately mark up local businesses, trucks, subways and housing).

In 2008, it was TATS Cru to the rescue. David Gonzalez of The New York Times City Room Blog recalls the story of how it all began. A “sprawling warehouse” owner called on the help of TATS Cru to paint murals on his walls to keep vandals away. The idea spread throughout Hunts Point, making it one of the best-known areas for this kind of work, and also the home to TATS Cru at 940 Garrison Avenue. Back in 2008, TATS Cru put out the call for artistic collaborators on a Friday, and “that was all it took to summon more than a dozen of the city’s best known graffiti artists to an otherwise desolate stretch of Hunts Point” (Gonzalez). Together, they turned the 200-foot long stretch of bare warehouse wall into an eye-catching piece of art. Much enjoyed by the warehouse owner, the mural caused long-time residents of Hunts Point to stop and look, which was just what TATS Cru was hoping for. Continuing their work since then, Wilfredo “Bio” Feliciano, BG183 and Hector “Nicer” Nazario, who make up today’s TATS Cru, have been on a mission to bring Hunts Point to life, as well as to bring Hunts Point life to light, through graffiti art, one wall at a time.

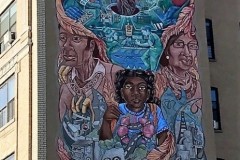

Beginning on Drake Street, I was rather confused to find just one stretch of wall with graffiti art, the typical tagging or lettering that one associates with graffiti, as I was under the impression that Drake Street was the main hub for the artists’ work. Rounding the corner and around the block, however, I came upon another mural, this one of 1990s cartoon characters, stretching even further than that of the mural on Drake Street. You can tell from the paint which mural was done first, and if you look close enough at the details you can even find the date of composition. The mural on Drake Street was done recently in 2017. Continuing on my journey, I set out to find the home of TATS Cru, as I was sure I would find more to look at. Happy to find that it was a quick five minutes from where I was at the corner of Spofford Avenue, I kept my eyes open for more hidden murals. What I came across on Hunts Point Avenue was nothing close to hidden, but rather large, in your face, colorful, cultural murals with deep messages. The messages found within the art are among the most compelling and interesting details to look for. One mural that took up the entire side of a tall brick building depicted two Latina women working to bring sunlight and water to their community so as to help it grow the way Mother Nature would nurture a plant. The message reads, “You Don’t Have to Move Out of Your Neighborhood to Live in a Better One.” Below the mural on the fence are portrait murals depicting the many diverse faces of Hunts Point. Across the street, upon looking up, an even more in-depth, collaborative mural becomes visible, depicting yet again the diverse faces of Hunts Point and its people. What I realized was that what was once considered by some to be graffiti vandalism in the area had grown into a movement of solidarity among community members. These murals were getting Hunts Point residents and visitors alike to stop, look around, and observe their neighborhood and community in a way in which they would not have before. The next mural’s message read “Don’t Move. Improve.” It showed the face of a young girl depicted through vibrant color while her parents’ faces behind her and the detailed painting of the neighborhood were in muted tones, sending the message that children are the future and have the ability to bring Hunts Point back to life.

Pedro Pietri, one of the great Nuyorican writers of the recent past, writes about these very ideas in his 1973 poem “Puerto Rican Obituary,” where he expresses the regret of past New York Puerto Ricans who often died wishing for more: more for themselves and more for their communities. The faces of the TATS Cru murals are like current representations of the faces of Pietri’s “Juan / Miguel / Milagros / Olga / Manuel / [who] All died yesterday today / and will die again tomorrow” (1358) were it not for the present-day community movement expressed through TATS Cru’s graffiti art and neighborhood cultural coalitions like it. TATS Cru’s “Don’t move, Improve” message can be read as a response to Pietri’s description of impoverished Latin@ neighborhoods in the 1970s—“From the nervous breakdown streets / where the mice live like millionaires / and the people do not live at all” (1359)—a harsh reality which some living in Hunts Point still face today. TATS Cru and other Hunts Point graffiti artists have taken that lifestyle and supposed lack of opportunity that past- and present-day Latin@s and other minorities have too often been made to endure and turned it into the vibrant community movement that we see on the walls of Hunts Point buildings, turning their art into a creative business and community asset.

Not all murals in Hunts Point are signed by TATS Cru, showing that they are open to sharing their open-air gallery with other artists. They, in concert with other graffiti artists of the first order, are making sure the message is out that no one should be forced any longer by their circumstances or ethnic and racial discrimination to be the “assistant, assistant, assistant / to the assistant’s assistant” (Pietri 1362). One mural at a time, these artists are sending the message that Hunts Point “Juans” never have to die “hating Miguel because Miguel’s / used car was in better running condition / than his used car,” and Hunts Point “Milagros” never have to die “hating Olga because Olga / made five dollars more on the same job” (Pietri 1362). In fact, Hunts Point’s Juans, Miguels, Milagros, Olgas and Manuels can now walk their community’s streets and look up to see their own faces portrayed on the walls in the most positive, affirming manner, knowing now, if Pietri feared they did not in his poem, “that they are beautiful people” who can admire “the geography of their complexion” (1363) thanks to the intervention of TATS Cru and other artists. If you are looking for a place where community and creativity connect, a place where graffiti artwork is a progressive movement, get to The Point.

Works Cited

Garcia, Sandra E. “The Rich History of Hunts Point.” The Bronx Journal, 10 Dec. 2011, bronxjournal.com/?p=7383.

Gonzalez, David. “In the Bronx, Painting Together at an Open-Air Gallery.” The New York Times, 20 Mar. 2012, cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/20/in-the-bronx-painting-together-at-an-open-air-gallery/.

Pietri, Pedro. “Puerto Rican Obituary.” The Norton Anthology of Latino Literature, edited by Ilan Stavans, Norton, 2010, pp. 1357–1364.