Revisiting Tom Wolfe’s Bronx “Jungle”

In a tense moment early in Tom Wolfe’s satirical novel The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987), Sherman McCoy speeds through a red-light signal, hoping just as speedily that some cops will catch him and save him from greater threats. Sherman, you may remember, is white. A wrong turn has brought the self-proclaimed “Master of the Universe” and his mistress into the borough of “dark faces,” more “dark faces,” whole packs of them. Imagine the white Manhattanite’s terror. Dark faces. The Bronx. When “human existence had but one purpose: to get out of the Bronx,” as the novel puts it, it is the narrator’s way of communicating that the Bronx is not a place fit for human habitation. Sherman would agree.

Naturally, given this racial othering of the brooding, dark Bronxites and the danger they supposedly present to white Manhattanites like Sherman, when Bonfire came out in 1987, there was a hue and cry. The neglected borough had had it. Wolfe, they thought, had to be held accountable for “the negative stereotyping of just about every ethnic and racial type known to New York City” (Wolfe qtd. in Plimpton). Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer, in particular, was upset. Very upset, even: “It would be too easy to say that it’s a slur on the Bronx, that it’s a cheap shot and a bad characterization of the fine and wonderful people who live in this borough—all that would be true.” No, Ferrer continued, mustering a not-so-veiled threat that could also be construed as an apparently unconscious act of gay-bashing in his own borough, “I guarantee you a guy like Wolfe”— although straight, Wolfe was famous for dressing like a dandy in white suits—“wouldn’t last five minutes in Belmont, let alone the South Bronx, walking around dressed like that” (qtd. in Erlanger).

In the novel, the cops Sherman so eagerly hopes for never arrive. He and his mistress, Maria Ruskin, circle round and round the Bronx in his $48,000 Mercedes, no way out of the “nightmare terrain.” The South Bronx is a dark labyrinth that the white investment banker cannot navigate, not even in his imperial vehicle, his Mercedes-Benz. When there finally is a chance for the two to get back onto the expressway, the ramp is blocked by a tire. Scared, Sherman gets out of his car to remove the obstruction when he is approached by two black men—“Yo! Need some help?” offers one, who he assumes plans to rob him—or worse. By now, Sherman’s white paranoia has disposed him to see the borough as a jungle: an unknown, uncivilized terrain where fear and “dark faces” abound and predators await in the dark to mug their (white) prey. His white mistress, equally paranoid, grabs the wheel and accidentally hits one of the men, causing a serious (and ultimately fatal) injury. The two lovers rush back to Manhattan. Sherman experiences some guilt and misgivings initially, but it doesn’t take long for him to own the experience as a victory. He emerges from the Bronx crowned as the “King of the Jungle”!

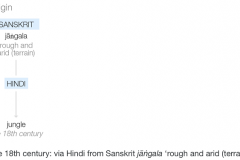

The word ‘jungle,’ of course, evokes colonial connotations. (Indeed, it is for these very connotations that Wolfe seizes on the term in his satirical novel.) The word entered the English language from the Sanskrit ‘jāṅgala’ early in the British rule over India, that is, the late eighteenth century. In India, white men had entered an unknown terrain and had assumed hierarchical control over its residents simply by the virtue of their being white—which meant, to them, more civilized—and by having the power to impose their rule. Sound familiar?

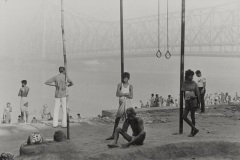

The unknown terrain was branded a ‘jāṅgala’, a jungle: lawless, savage, wild, chaotic, a labyrinth, and the inhabitants were given attributes accordingly. Such racial othering was a common practice in the West and remained one late into the twentieth century when Wolfe’s novel appeared. Even The New York Times, supposed to be a beacon of liberal progressivism, expressed its fears of urban decline in New York City through racial othering, or, as we might put it, “jungling.” A July 15, 1987 article, published the same year as Bonfire, reported that “as thousands of homeless and deranged people [were] camp[ing] out on the streets” and poverty and starvation were in plain sight, New York City could be likened to Calcutta, now called Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal, in India. New Yorkers weren’t thrilled with the comparison. How dare the Times call New York City Calcutta! A week before India’s 40th Independence Day, an opinion piece ran in response under the not-at-all-misleading title, “Why New York City Is Not Yet, Thank Goodness, Like Calcutta.”

According to these folks, NYC (that is, Manhattan) was not yet like Calcutta, but commentators like Wolfe and Sherman and the authors of these articles were surely willing to cede that the Bronx was a lot like Calcutta: a nonwhite urban “jungle” populated by supposedly unruly people in need of being policed (when not colonized), limited and controlled.

The author Wolfe was not beyond defending this othering, or “jungling,” trope as part of his satire. In an interview with the Paris Review, he said his book merely “violate[s] a rule of etiquette,” meaning “that it’s all right to bring up the subject of racial and ethnic differences, but you must treat it in a certain way,” and that, in Bonfire, he simply hadn’t treated the subject in a way polite society finds permissible. We sometimes call what he is getting at “PC culture” today. In the name of refusing to honor a rule of etiquette, and under the guise of “equally directed satire,” Wolfe centered his plot around white fears of “dark faces” and the corpse of a black boy whose death will ultimately bring down the “Master of the Universe,” Sherman. Can such a plot, which dismisses the Bronx as a dark jungle and makes use of racial prejudices for the purposes of satire, ever be acceptable?

In March 2019, on a cool morning of early Spring, I decided to visit the scene of Sherman’s abasement, the Bronx County Courthouse where he is tried for the murder of the black boy whom his mistress ran over in their escape from the Bronx. I took the only way I could to get to this building that Wolfe calls a “Gibraltar.” I got off the train at Yankee Stadium, which is surrounded by a huge parking lot because the mainly white spectators who come to the ballpark are not going to venture more than a block into the Bronx. Up a little hill from the Stadium, there is a similar, fortress-looking building, my destination. Only this other fortress is a courthouse, with power being more palpable here. As I passed through the security check, I wandered into a not-so-familiar setting. “It’s Friday, nothing juicy happens on a Friday,” a lady guard said — something anyone whom I approached agreed with. Someone finally directed me to a trial in which a Jewish doctor was being sued by a Latina patient. The makings of this trial seemed to have the same racial and ethnic antagonisms that Wolfe showed to be at the heart of the city’s conflicts, antagonisms that come out of the clashing factions that make up the city’s diversity.

In March 2019, on a cool morning of early Spring, I decided to visit the scene of Sherman’s abasement, the Bronx County Courthouse where he is tried for the murder of the black boy whom his mistress ran over in their escape from the Bronx. I took the only way I could to get to this building that Wolfe calls a “Gibraltar.” I got off the train at Yankee Stadium, which is surrounded by a huge parking lot because the mainly white spectators who come to the ballpark are not going to venture more than a block into the Bronx. Up a little hill from the Stadium, there is a similar, fortress-looking building, my destination. Only this other fortress is a courthouse, with power being more palpable here. As I passed through the security check, I wandered into a not-so-familiar setting. “It’s Friday, nothing juicy happens on a Friday,” a lady guard said — something anyone whom I approached agreed with. Someone finally directed me to a trial in which a Jewish doctor was being sued by a Latina patient. The makings of this trial seemed to have the same racial and ethnic antagonisms that Wolfe showed to be at the heart of the city’s conflicts, antagonisms that come out of the clashing factions that make up the city’s diversity.

Thirty years have passed since Bonfire came out, but the book continues to rankle in its representation of the Bronx and its majority nonwhite population. It also remains prescient in its analysis of white capitalist power and racial resentment. Not by coincidence, in the same year Bonfire was published, another work called The Art of the Deal appeared by another white Manhattanite who now specializes in othering, “jungling,” and mistreating minorities, be it through his insistence on a wall, his ban on people of certain faiths, or his caging of children, traumatizing and sometimes even losing them in the process. Bonfire is not The Art of the Deal, but to some of Trump’s neocon ideologues, it reads the same. They see in Bonfire’s Sherman a white male victim of the nonwhites (Weideman). They see themselves, misunderstanding entirely that Bonfire is a satire, that Tom Wolfe’s Bronx “jungle” never existed. Yet even with this qualification, to the rest of us readers, Wolfe’s Bonfire is a satire gone sour.

Works Cited

“Dumped on the Citizen’s Doorstep.” The New York Times, 15 July 1987, www.nytimes.com/1987/07/15/opinion/dumped-on-the-citizen-s-doorstep.html.

Erlanger, Steven. “Bonfire in Bronx!!! Wolfe Catches Flak!!!” The New York Times, 11 Mar. 1988, www.nytimes.com/1988/03/11/nyregion/bonfire-in-bronx-wolfe-catches-flak.html.

Plimpton, George. “Tom Wolfe, The Art of Fiction No. 123.” The Paris Review, 14 June 2018, www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2226/tom-wolfe-the-art-of-fiction-no-123-tom-wolfe.

Weideman, Reeves. “The Duke Lacrosse Scandal and the Birth of the Alt-Right.” New York Magazine, 14 Apr. 2017, nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/04/the-duke-lacrosse-scandal-and-the-birth-of-the-alt-right.html.

“Why New York City Is Not Yet, Thank Goodness, Like Calcutta.” The New York Times, 7 Aug. 1987, www.nytimes.com/1987/08/07/opinion/l-why-new-york-city-is-not-yet-thank-goodness-like-calcutta-884387.html.

Wolfe, Tom. The Bonfire of the Vanities. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, Nov. 1987.

_________

Hardik Yadav is an Indian-born student of (Honors) literature. His interests lie in literary, movie, and TV criticism; ask him about Barthes, Bollywood, and Barry (HBO).

To do good every time..

Congratulations..!!

Thank you for writing this Hardik. In my Art and Thought of the 1980s class at the Graduate Center, we just wrapped a discussion of Bonfire of the Vanities. I’ve learned even more through your thoughtful analysis of the reception of Bonfire in the 80’s. In class, we imagined how reading this text as horror might awaken just how dehumanized some of Wolfe’s characters actually are, something I think pairs quite well with your point about how scared the general public was at the possibility of NYC resembling Calcutta. What was it that the public was scared of in that comparison?

-Dhipinder Walia