“Lofty Geometries”: Poetry of the Bronx Bombers

Walt Whitman once said, “I see great things in baseball.”1 Seventy years later, at seven years old, I saw great things in the New York Yankees. In front of Hammersjold Drugs in Graettinger, Iowa, in the flashing light of the town’s only electric sign, I opened my first pack of baseball cards on a Saturday night. Inside the sealed wax pack was outfielder Hank Bauer’s card—which was number 8 that year—among the first cards included in six-card nickel packages with a stick of gum. I was mesmerized by Bauer’s toothy grin and the nonchalant way his cap was cocked back upon his head. But I was even more entranced by the Yankees logo in the card’s bottom-right corner. Seeing a bat donning a star-spangled top hat not only seemed mystical to me but was “slant” like the poems I’d later read in high school.2 It was poetical! I knew at that moment that I would be a Yankees fan!

It had little to do with my decision to cheer on the Yankees, but nearly everyone who followed baseball in northwest Iowa was either a Yankees or Cardinals fan. And, of course, at age seven, I wasn’t negatively influenced by the quote that was making the rounds, that “rooting for the Yankees was like rooting for US Steel.” And, of course, had I heard it, I likely would have loved my Yankees even more. From the first I was enthralled by a lineup that included Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Elston Howard, Bobby Richardson, and Tony Kubek, and hurlers such as Whitey Ford and “Bullet” Bob Turley.

My debut book of poetry, The Ripening of Pinstripes: Called Shots on The New York Yankees, was issued by Story Line Press in 1998 after being a runner-up for The Roerich Prize in its national contest for first books. Although not published for another three years, I had actually finished Pinstripes in 1995, a year prior to Derek Jeter’s rookie season. In the spring of ’96, I attempted to write a poem about the young Jeter that was meant to be the final poem of the collection. But without showing anyone, I knew that the poem had failed.3 I never planned to write another Yankees poem, but on a whim this past summer, I found myself again writing one about Jeter, the now-retired star Yankees shortstop, but, of course, it was a different poem altogether.

In the years since Pinstripes appeared, I never lost interest in my Yankees. I followed them on television, in the newspaper, and by watching the team’s games on the computer, viewing the Yankees broadcasts on the YES network, and listening to Michael Kay, Paul O’Neill, and David Cone. Friends have encouraged me to write more poetry about the team.

In my mind, no matter how they finished in the standings, the Yankees always gleamed, just as they did in a dream one night in Iowa, sixty years ago, when I was age nine or ten, and watched the team bus drive up our sunny quarter-mile farm lane. They had just played a series against the Twins in Bloomington. All the Yankee players, from Mantle and Maris to Bobby Murcer and Tom Tresh, sat at tables throughout our house, eating fried chicken and mashed potatoes. When Father was busy picking corn or putting up silage, Mother had often served neighboring farmers. How appropriate it seemed, that the Yankees were visiting, maybe on their way to Kansas City, and stopping to eat their noon meal. How appropriate, it seemed, that the double-play combination, Richardson and Kubek, sat side-by-side at a table. We were quickly on a first-name basis. They confided to me how different it was to play under Ralph Houk than under Casey Stengel. They punctuated their conversation with pats on my shoulder and told me what I longed to hear, that even at my tender age, I’d make a fine Yankees manager.

Instead, I became a poet.

–Rodney Torreson

Cocky Whitey Ford Would Buck Up Even as His Curveball Collapsed I learned that year—1961—when I was ten, that you don't have to finish what you start. Whitey would go on to win 25 games. Manager Ralph Houk, the cigar- chomping major, could detect when his ace was tiring: his fastball couldn't saw off a batter, or his slider grew wider across the plate. Then Houk would raise a finger, signal the bullpen for Louis Arroyo. I was a starter too, of English assignments in junior high, but would neglect to complete my work. At the next class, when the teacher would ask us to take out our papers, open our books. I'd do a bone-lonely thing: crouch behind the girl in the seat in front, knowing no screwball friend would step from the hall, finish my paper, turn in a good performance. I'd get no credit, no win, not even zeroes posted on the scoreboard that worked in the Yankees’ favor, like Arroyo did for Ford.

How Fitful, Lou Piniella, that in the Bad Apple Boos Blew Through Your At-Bats Each barrage showed that fans loved you. Their drones of "Lou! Lou!" swept from the upper deck to the grandstand, through concessions with their bottlenecks of fans—some in the throes of transistor radios. Lou, you’d settle in at the plate like a fighter pilot—your bat grinding down pitches till you got one you liked. In truth, your .291 batting average leveraged each at-bat, so your plodding feet led to disappointments—with your ground outs especially hard to watch. The Yanks were so good, though, it only felt like a drubbing each time you’d hit into a double play, the infielders rubbing it in with a flip to second, the transfer polite as any handshake. Then the precision of the peg would get you still lumbering toward first. At least it was quick. We moved on from it. But you were a fine player, Lou, for your hard play and instincts from the thickets, as in '78—that one-game playoff, the last inning—two frames past Bucky Dent barely clearing the Green Monster for what would be the game-winning homer. In the ninth, Jerry Remy lined one to right. No one need remind you that you lost it in the sun, for every day you likely lose it yet again for the next forty-four years, and each day you're redeemed when your glove finds it again. For somehow that ball in blinding sun gets embroiled in our hopes and fears. Yes, you lose Remy's drive, but almost gloriously hold out your glove in one of the game’s greatest cons. The sudden ball thuds the ground eight feet in front of you, and not seeing it you finally flail your glove as if drowning. If the ball buzzed your mitt, it would have been a miracle itself, turning screws on the circular season to bring us to spring, for what Yankees' fan cares what occurs if the Yankees fail to win. The ball, though, smacked into the mitt's pocket. Lou, you snapped and locked it—rifled to third, kept Rick Burleson from having the nerve to try for third and stymied Remy, who'd hold up at first. Neither scored. The Yanks would win 5-4, as you and your teammates came down from high in the smallest elocution of sky, leaped into October heaps of happy bones.

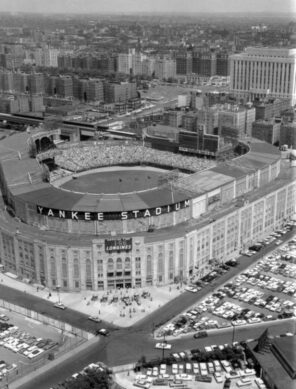

At Yankee Stadium, in '22, Among Grand Standing Shadows and the Stir of Streets Hitters from the Sultan of Swat to Aaron Judge tie themselves up in their swings. Still, The Babe, who batted left, pulverized pitches. Judge towers blasts from the other side. Before they fade in their arc, there’s an instant when a ball may stall in summer air, so fans can take it in. Not once has Judge felt the slippage of a pillow, to suggest it’s all a dream. Babe’s glove always smelled like green grass. But at an exhibition game in Miami, it was the air that was riotously rich, so when Babe saw a palm tree in center, he didn’t know for sure it was there till he knocked himself out running into it. Judge, though, contends with no tree, but to catch a ball that would be over another outfielder’s head, he leaps toward the ball’s trajectory— not catching his cleats on the wall and with steps climbing up to it. With a gleam in his eye, Babe basked in beer, swearing, and running with women not his wife. Judge courts a girl from the wild side and marries her. How easy to carry her over the threshold. Judge, that humble hulk, is on pace for more than 60 homeruns, as well as to wire the stars into place. Each year with a marker he scrawls .197 inside a shoe to remind himself of his rookie batting average. Beneath his white pinstripes was darkness he hid until the renewal of his contract. But as a free agent he leaves everyone stunned by having flings with other teams. For leverage he’ll bandy a suitcase about. Babe sometimes stood atop the Yankee dugout while his lungs, those meaty amplifiers, taunted fans to a brawl, shouting down the darkness, never owning up to his shadows. Babe filled a mirror without self-reflection. Judge’s muscles never mug for a mirror. And his biceps merely whisper as he keeps the looking glass empty except for his swing. And when he runs the basepaths or across the field, his polite elbows flow. There is also the light of his lope and a suggestibility of wings. Even with his 6 ft. 7 frame and weighing two hundred eighty pounds, his feet don’t clop. Instead, he gives out more light in his footsteps breathing up.

Matt Carpenter, I imagine You at 36, Riding a Big Bare Moonbeam "In 79 at-bats with the Yankees Carpenter is slashing an incredible .354/.469/.911 accompanied by a 1.380 OPS and 13 home runs." –Terron Morris, "Matt Carpenter Revitalizes Yankees Heading into Break," July 21, 2022 Even in the batter’s box, you warp time as the thick bush on your upper lip takes us back to Mattingly’s mustache, and further, to the '50s, when billboards buried outfield walls. Your left-handed upper swing doesn't need wings. Each drive is lashed onto a sky track beyond the shift and shadows, not the case your final years in St. Louis. No moonbeam at all in '21, when your season highlight was being sent into pitch, to mop up a lopsided contest. Now with the Yankees, the one team to call when the Rangers dropped you, light tightens around your frame, as you take baseballs to the woodshed, though at the same time you rise above your swing, then higher toward the galaxy's grandstand before the All-Star break. On that one day you went 0 for 4. No color man needed to describe your forlorn face when the camera panned the dugout, which likely happened again last night, June 26th, as if the lofty geometry were short-lived, while fans wonder if bruised light caught up with the swing you'd found in the off-season—the cloth of your return now ragtag towels in some old motel in the minor leagues, and us tempted to have our faith fall in, that a comeback can't latch onto a moonbeam, that it's surely folly trying to flower.

Notes

1 On the attribution of this quote, see https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-xpm-2012-mar-28-la-sp-sn-bull-durham-baseball-20120328-story.html.

2 “Tell all the truth but tell it slant —,” writes Emily Dickinson, in one of her most famous lines.

3 Jeter was then being touted as the greatest Yankees prospect to come along in years and was earning plaudits for his wholesome good nature. This had been confirmed for me by two young people who had taken the same high school gym class with him. They sang his praises. Yet despite his being from neighboring Kalamazoo, Michigan, only fifty miles from where my family lived in Grand Rapids, in 1996, I couldn’t latch onto a sound poetic idea.

The former poet laureate of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Rodney Torreson has won the Seattle Review‘s Bentley Prize, and his poems have been featured in former US poet laureate Ted Kooser’s syndicated newspaper column “American Life in Poetry.” Torreson lives in Grand Rapids, where he taught creative writing at Immanuel St. James Lutheran School for 32 years. In addition to The Ripening of Pinstripes (1998), he is the author of the collections The Jukebox Was the Jury of Their Love (2019) and A Breathable Light (2002). His fourth full-length collection, a book of urban and rural poems titled The Ascension of Sandy’s Drive-In, is forthcoming from Kelsay Books. He holds an M.F.A. from Western Michigan University.