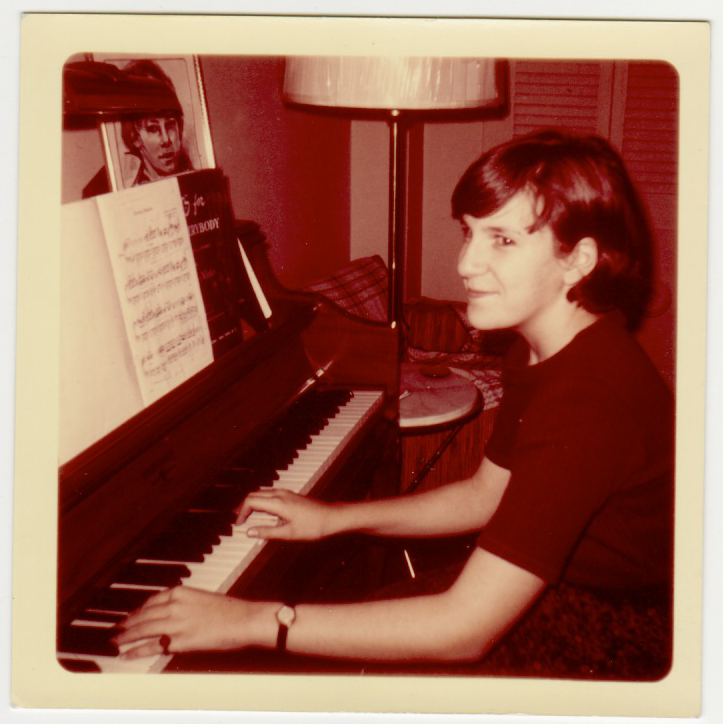

Scenes from Childhood, 1965

This is the Bronx, and you will find beauty here only unexpectedly. The street names lack resonance; no one dresses with style; the usual complaints are made on the supermarket lines.

The absence of things to see kept me indoors when I was young. I didn’t want to belong to this borough of broken sidewalks and looming apartment buildings: I never dawdled by the benches of the playground with boys and girls my age. I sat in my room reading of horseback rides at night, of duels, of happiness achieved, and daydreamed of mountains and castles far from our eleventh-floor apartment. Or else I looked across the street at a thin tree, its leaves a shiny green in April. When the wind rode down the hilly street, the leaves shook: the shadows of the branches moved on a red brick wall. There was my beauty.

Our household was consecrated to two ideas, both my mother’s. She had made herself a marshal of order and cleanliness. Everything had its place, including me, but it is hard for youth to understand that sort of perfection. I was often found out of order: reading when I ought to have been practicing the piano, or standing by the open refrigerator, snack in hand, just before dinner. My mother would discipline me with a quick slap. My father would ambush me. “Who eats a slice of cheese before dinner?” How lonely I felt when posed a question that had no answer!

My mother believed in her second idea as fervently as the first. When she and I were alone, she told me of the insults she suffered from my father’s family. As a child I failed to grasp whatever nuances pricked her. In her repetition of my grandmother’s “insults,” I heard only the tiresome talk of adults.

At the age of eleven I was briefly inspired to devote my life to God. I would be a nun. We were Jewish; all I knew about the religion of nuns was that they lived together. I thought the old stone house near our synagogue could serve as a Jewish nunnery. Dressed in blue and white, the colors of Israel, I imagined living there, away from my parents, and talking to no one. Every day I would go to prayers. For how beautiful were the voices that sang the Etz Chaim as the Torah was carried around! My spirits soared when a woman’s voice hovered above the singing congregation.

I told my mother.

“Jews can’t be nuns,” she said in anger.

We were in the living room. She was reading the newspaper with her half glasses and although it was getting dark, she hadn’t yet turned on the lamp. I had nothing to do. I dared not read the book I bought that afternoon: if she saw it, she would not like it. I didn’t want to practice the piano and break the stillness, which I thought was holy. I sat on the rug, my knees drawn up to my chest and looked out the window at the blank autumn sky. I shut my eyes. “There is nothing,” a voice—my bad angel—said. I opened my eyes, afraid of something indefinable and saw that the living room had continued placidly as before. I closed my eyes again and tried to draw something holy out of my fears.

She switched on the lamp at the same time that my father turned the key in the apartment door lock. I opened my eyes to see my mother glance from the newspaper to her watch. “Hello,” my father said to us as he stepped into the foyer. His voice had a sarcastic tinge; already we were in his dull, pedantic grip. He hung up his coat and laid his vinyl attaché case on the hall cabinet. My mother did not say hello. She folded the newspaper and, as she put it on the footstool in front of her chair, said, “She wants to be a nun.”

My father had come into the living room.

“A nun?” he said. I felt his stare. I got up from the rug.

“Oh, forget it!” I said and went into my room.

As I closed my door, I heard him say “nun” again, before he went to the bathroom to wash his hands for dinner.

I looked at myself in the dresser mirror. My long face told me nothing about myself.

I heard the bathroom door re-open; my father passed my room and now they both were in the kitchen. I could hear them.

“—she doesn’t do her homework, she comes home late from school and lies around!”

“—wind up behind the cash register in Woolworth’s! You’ll have to—” but I wouldn’t listen to them anymore.

I pressed my chin against my neck to have jowls like him. “A nun?” I said to the mirror mimicking his voice.

“She wants to be a nun,” I told my reflection.

“A nun,” I repeated solemnly and stared at the mirror as my father had stared at me.

But I felt glorious.

I had stumped them. Forgetting my desire to be a nun, I went to dinner feeling pleased. “You have nothing and no one but yourself,” I thought. But I also had the book I had bought that afternoon.

“Pay it and get it over with,” said my mother.

There was a discussion at dinner.

My father did not want to pay the amount stated in a letter from the housing office.

“I’ll go see Silverman,” he said.

“When?”

“After dinner.”

My mother made her lips tight. My father stabbed his green beans ruthlessly with a fork. I pushed the food around on my plate. They always fought. They always would: they are children, I thought, holding myself above them.

“Once you’re home, you should stay home,” my mother spoke.

“Is it written in the Torah?” he answered.

She gathered up her plate and silverware while he was still eating and went into the kitchen. The notes of a Schumann Arabesque twirled into the dining room from the kitchen radio. I listened to the perfect notes of the piano.

“Why aren’t you eating?” my father asked.

“Not hungry.”

He gave me a meaningful look but looks never revive one’s appetite.

My mother washed pots. Above the music and the roar of the water, she shouted, “He doesn’t even know Silverman, but he’s running there in the middle of the night.”

The music continued. It was lovely. I ate a few cold string beans. “Too god-damn cheap to pay, that’s all!” my mother shouted at the kitchen sink. “Him and his stinking family!”

Then she brought me a cup of applesauce. I scooped some up and held the spoon in my mouth. My tongue rested on a cool, soft, grained bed. I removed the spoon to look at the depression my tongue had made, and lick by lick, with the tip of my tongue, I ate the applesauce. The coolness of it caressed my lips while my mother clinked the plates as she put them away in the cabinet.

My father looked at his thin watch. “It’s six-thirty and I do know him, dear.” He said “dear” in his poisoned way: it was a quick snake let out onto the floor. My father rose from the table, washed up, got his hat and coat and left, locking the door with vigorous clicks.

When she finished all the dishes, my mother went into the living room and turned on the television. She sat down in her armchair to watch people laugh on the black and white screen.

“Why don’t you sit with me?” she called out, but I thought I could read my book now. I pretended I hadn’t heard and went into my bedroom.

Out of duty I opened my notebook to the vocabulary homework first. Jettison, corpulent, panacea: I did not know these words. I read the dictionary entry for jettison but remembered nothing. I resisted the book no longer.

A month ago, I had overheard two teachers in my junior high school talking about a book called A Spy in the House of Love.1 The words of the title were like an enchanting wisp of blue smoke above a pine forest. I thought the House of Love must be something splendid, rich and shining, a house of happiness. The word ‘spy’ gave the title a sweet thrill. I whispered the title to myself in the halls at school and at night in bed. I loved the words but they frightened me, and for protection I would sing the Shema softly into my blanket:

Shema Yisroel Adonai Elohenu

Adonai Echud.

I saved my allowance, skipping gum and lifesavers, so that I could buy the book. My parents had begun to allow me to take the bus with a friend to the shopping district on Fordham Road. Before coming home that afternoon, I had gone to the bookstore on Fordham Road and the Grand Concourse. Not wanting to say the title of the book out loud, I did not ask a store clerk for help. I stood in the paperback book section, scanning the shelves from A until N, where I found the book. I held it in my hands and gazed at the black-and-white cover. My friend, impatient, dragged me to the man at the cash register. Possibly he would not allow me to buy it—the word “love” was almost forbidden in my house. But the man had a mustache and thick unkempt brown hair; he took the pipe out of his mouth, glanced at the book in a bored way and rang up the machine.

Now, with my mother watching television, I pulled the book out of my bag. The glossy cover felt slightly damp under my warm fingertips.

The book opened with a delicious crackle. How smooth were the pages! I turned them slowly, one by one, until I reached the beginning of the story. I read the first paragraph, then the first page. It was incomprehensible. Stunned, I closed the book on my desk and looked at the lights in the apartment houses across the street.

My mother banged open the door.

“Didn’t you hear me call you? What are you doing?”

“Reading.” But my book was closed.

“Reading what.” It was an accusation. She stood behind me and reached over my shoulder for the book. I felt the nap of her flannel housecoat; she was so close to my cheek that she could have been giving me a kiss.

“What kind of book is this? What kinds of things are going on in here?”

There was no answer.

She held up the book like a paddle.

“Where did you get this trash?”

If I told her she might not let me take the bus with my friend.

“I found it.”

“You found it!” she scoffed at me. “You’ll find a whack on your behind if you bring this kind of garbage home again. ‘House of Love’! Wait till Daddy gets home.”

She took my book and made a show of keeping my door wide open.

I would not let her upset me. I stared at my blank homework page. Tears filled my eyes but I blinked them back. My expectations had been wrong, and my childish pride was pierced. Mystery, Beauty, Love—all been pulled away from me.

I had no stomach for the words on my vocabulary list.

A native of New York City, Beth Adelman has won two awards for fiction from the Bronx Council on the Arts and has published short stories online at Bodega and WORK as well as in the Jewish Literary Journal and Jewish Fiction. A novel excerpt appeared in Brilliant Corners, a print journal of jazz and literature, in May 2018. “Scenes from Childhood, 1965” was previously published, in slightly different form, in Woven Tale Press Magazine, vol. 6, no. 6, in 2019.

Notes

- A 1954 experimental novel written by French novelist Anaïs Nin. ↩︎